As the balance of production and consumption between the United States and China sways back and forth, our North America Economist Marcos Carias shares his latest insight on the supply chain shuffle.

Decoupling challenges between U.S. and China

Though we should always be careful not to read too much into a handful of data points, it’s hard to look at recent figures and not see how much of an uphill battle Sino-American trade decoupling will be. Across the pacific, China’s deflationary woes aren’t getting any better, with headline inflation falling to just 0.4% in September, and producer deflation accelerating to -2.8%. Wait … lower prices … isn’t that a good thing? Not when they’re coming from a lack of demand. In this case, the numbers show that China’s industrial prowess won’t be very useful if it can’t maintain its presence in foreign markets, with the Chinese consumer all but missing in action.

A global consumer of last resort

Meanwhile in the United States, we had a stickier-than-expected inflation print at 2.4%. On its own, nothing too remarkable, but it comes on the throes of surprisingly good job numbers and, most importantly, data revisions suggesting that household balance sheets are healthier than previously thought. As we approach election season in November, the next U.S. president will probably seek to further boost household purchasing power. For all the daylight between candidates Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump, they seem to agree on one thing: running up the deficit to put cash in the consumer’s pocket. Bottom line: we have every reason to believe Americans will continue to be the global consumer of last resort for the foreseeable future. In contrast, industrial policies (i.e. what the U.S. would have to do to make, in-house, a larger part of the goods it consumes) aren’t looking like the hottest talking point in this campaign.

A source of opportunity

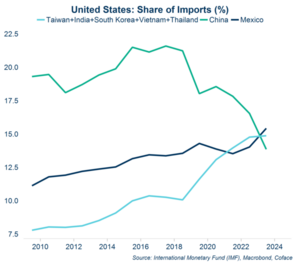

The fact is, the U.S. accounts for 29% of global consumption (but 13% of tradable goods production), while 27% of tradable goods are made in China (though China is only 27% of global consumption). Can the world champions of production and consumption live and thrive without each other? They’re certainly trying. Since 2017, the trade war has led to an almost 8-point decrease in China’s share of U.S. imports. Yet what is emerging in lieu of the Sino-American relationship is an archipelago of emerging economies (notably Mexico and Vietnam) building trade and investment links with both parties. These shuffling supply chains are a source of opportunity, but also leave firms exposed to the whims of international relations, beginning with the White House’s unpredictable trade policies.

To dig into the intricacies of this timely topic, check out our Focus, Coface’s deep dive publication series.