Tuesday's election results may have major implications for trade, taxes, and rates (to name a few). This blog from our North America Economist Marcos Carias answers four questions you might be asking yourself in the final days before the 2024 U.S. election.

So, who's gonna win?

We don't know, nobody knows. The election polls are imprecise and the prediction models uncertain. Observers would do well to discount media hype around "momentum." Yes, we see a clear trend favoring former President Donald Trump in recent weeks, but leads against Vice President Kamala Harris remain well within the 3-4 point error margin. In other words, the polls are too inconclusive to tell us if said “momentum” is tipping the scales one way or the other.

Not only are the presidential hopefuls neck-and-neck, but both houses of the gridlock-prone, divided congress could flip (or not). Single-party control of Congress at the start of a presidential term has been the historical norm, occurring in 16 of the last 21 general elections, and in every one since 1988. However, the current majorities in both chambers of Congress are razor thin. In the House of Representatives, Republicans hold an eight-seat majority – one of the smallest in U.S. history – while Democrats control the Senate with a one-seat majority that includes four independents who caucus with them. Local opinion polls indicate a reasonable chance that both chambers could flip, resulting in a split Congress for the 119th legislative session (2025-2027).

Republicans, in particular, have favorable odds of retaking the Senate. After all, 23 of the 34 seats up for re-election are held by Democratic caucus members. With two to five seats likely to flip, it will be challenging for Democrats to win any of the 11 Republican seats on the ballot. However, Democrats have a decent chance of reclaiming the House, with 14 of the 26 toss-up races occurring in Republican-held districts. Democratic challengers are notably well positioned to win back New York’s 22nd district and Alabama’s 2nd district. Even if the elections result in a “trifecta” for either Republicans or Democrats, polling suggests narrow majorities, which will limit any president’s ability to translate their full policy platforms into legislation.

What a buzzkill. What happens to the economy if Trump wins?

Huge tariffs are coming, and huge tariffs are bad. You'll have heard about this ad-nauseum, but tariffs on the scale and spread that Trump has floated on the campaign trail (60% on China, 10-20% on all trading partners) would be a blunder, on balance. There is, on paper, room for tariffs to play a constructive role in the economy, if they are designed to target the specific industries where the U.S. wants to build autonomy. Indiscriminate tariffs, on the other hand, will hurt the margins of companies that rely on imported inputs, erode consumer's purchasing power, invite retaliatory tariffs, strain U.S. relationships with allies, and increase inequality (the lower your income, the more of your income goes into consumer goods).

Smaller government is coming and that's... a mixed bag. Republicans will seek to fully extend the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). In addition, they aim to lower the corporate tax rate from 21% to 15% and scrap taxes on Social Security benefits. To (partially) fund these cuts, Trump hopes to lean almost entirely on revenues raised from tariffs, whose collateral damage on internal demand should hit domestic tax collection. The platform is also heavy on scaling back regulation, particularly for oil and gas, but also healthcare, construction, and finance. Making it easier to build will help with the housing crisis, and it can be argued that the U.S., and the world still need a strong oil and gas capacity to prevent an energy crisis and conserve geopolitical autonomy. But here we get into the perennial trade-off between economic growth and environmental objectives... a debate beyond the scope of this humble post. Tax cuts, tax code simplification and less paperwork should be positive for competitiveness, but I would not bet on expenditures getting cut nearly enough to offset forgone revenues (gutting Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act will only take you so far). I would rather bet on a further deepening of budget deficits (more on that later).

Yikes! So is Kamala good for the economy?

Well... the best thing the Harris platform has going for it is the notable absence of indiscriminate tariffs. A simple virtue, but a laudable one. Beyond that, we mostly get continuity with the Biden administration's approach, with industrial policy taking a bit of a backseat to redistribution. TCJA income tax provisions should be renewed for all except the top bracket, which is in line with the pledge not to raise taxes on households earning less than $400,000 a year. Many of the platform’s social pledges would be achieved through tax credits, such as supporting families by enhancing the child tax credit, the $25,000 in support for first-time homeowners, and the expansion of the earned income tax credit for low-income households. The bulk of the burden would be carried by firms, with the increase in the corporate tax rate (from 21% to 28%), and increased taxation on high earners. Even if renowned trust-buster and Federal Trade Commissioner Chair Lina Kahn does not get renewed, we should expect a noticeably more hands-on approach to regulation compared to Trump. All in all, not exactly a boon for growth and competitiveness... but, again, preferable to tariffs.

Ok my head's spinning... what's the takeaway?

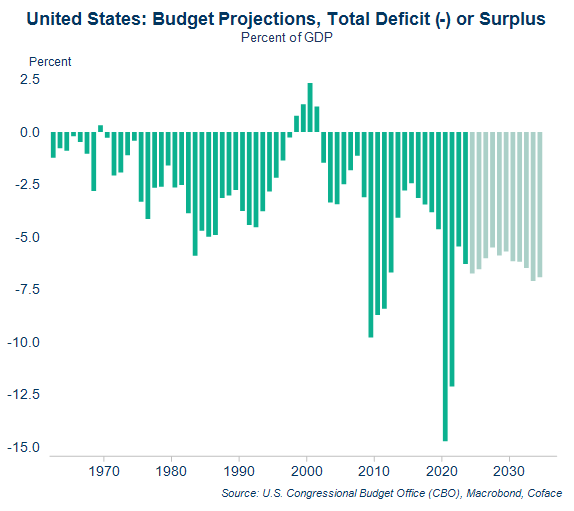

Trump and Harris offer two very different visions for the economy; small government and protectionism on one side, and big government and a last cry for multilateralism on the other. However, it's worth wrapping up by taking note of where they overlap. Both parties agree on seeing China as a strategic rival and will both seek to reduce trade dependence on the nation. Democrats will only be more careful with a more targeted and calculated approach to protectionism. Crucially, both platforms imply a deepening of the budget deficit, which is already historically large and will continue to deepen regardless of any changes to policy, according to projections by the Congressional Budget Office (see chart below).

Deficits are not inherently bad, but they should be reserved for giving a jolt to the economy whenever demand is too weak, like in the aftermath of the subprime crisis or the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. A Trump or Harris fiscal stimulus would be start in 2026 (TCJA provisions will expire end at the end of 2025), when the economy should be pretty close to full employment if nothing terrible and unexpected has hit in the meantime. Injecting extra purchasing power into an economy that's already producing/importing all that it can is a recipe for inflation. This was, in fact, one of the big drivers of the COVID-era inflation wave. The Federal Reserve will not be able to lower interest rates as much as it would like, making up for a harder funding environment.

Lastly, the U.S. government will continue playing with fire when it comes to debt (124% of GDP). Yes, fiscal hawks have been warning about an impending debt crisis for decades, only to be silenced by global investor's unappeased appetite for U.S. government bonds. This "exorbitant privilege" is afforded to the U.S. as the emitter of the world's still-unchallenged reserve currency, and the attractiveness of dollar-denominated assets. In other words, while the U.S. debt trajectory might look scary, the rest of the world still looks like a worse place to park your wealth. However, the persistently strong performances of gold and bitcoin should give us some pause here. The greenback is still the king of currencies, but fiat currency as an asset class could be losing credibility in a world where public debt is rising pretty much everywhere. Only time will tell how long the U.S. can coast on its “exorbitant privilege,” and that time may very well be much longer than one or two election cycles (right up to the day where it's not).

Marcos Carias is a Coface economist for the North America region. He has a PhD in Economics from the University of Bordeaux in France, and provides frequent country risk monitoring and macroeconomic forecasts for the U.S., Canada and Mexico. For more economic insights, follow Marcos on LinkedIn.