The U.S. election is over... now what? Our North America economist Marcos Carias talks us through the uncertainties and what to expect with the second Trump administration.

The U.S. election showed a decisive victory for President-elect Donald Trump and the Republican party with 57% of electoral college votes, 7 out of 7 swing states, full control of Congress, and the first Republican popular vote victory since Bush v. Kerry. With this verdict clear, the global conversation is shifting to, “How much of what was promised in the campaign will be implemented in full?”

When it comes to policy, details make a world of difference, and on this we’ll have to learn to live in suspense for a while longer. Tariffs? Coming for sure. However, will the Trump administration go for the big headline-grabbing numbers (60% on China, 10-20% on everyone else), or will we find those statements were simply a tactic to obtain bilateral concessions from our trading partners? And what about the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)? A repeal would need congressional approval, which may be hard to obtain given that the majority of IRA funds go to red districts.

This early in the game, rather than speculate on how much of this or that policy we’ll end up getting and when (our fancy graphs don’t allow economists to read politician’s minds… yet), this blog will focus on the things we can reasonably imagine about the future of the American economy under the second Trump administration. And one thing that is clear is more debt is on the horizon.

Debt and deficit: surfing on the wave of the exorbitant privilege

The budget deficit is simply the difference between government revenues and expenditures on any given year. On the campaign trail, Trump shared potential items expected to drive up the tab (mass deportations, for example) and others that could allow for savings (IRA repeal, closing the U.S. Department of Education, etc.). However, both are subject to a healthy dose of uncertainty: their scale can range from symbolic to significant, if occurring at all.

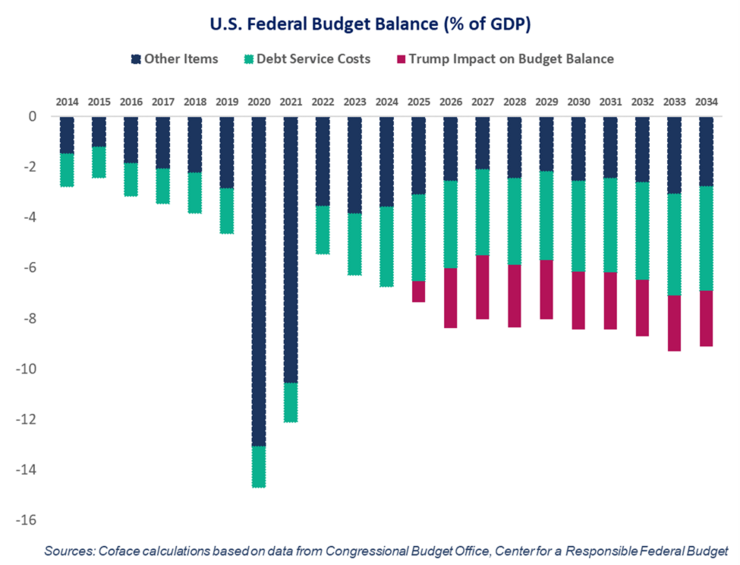

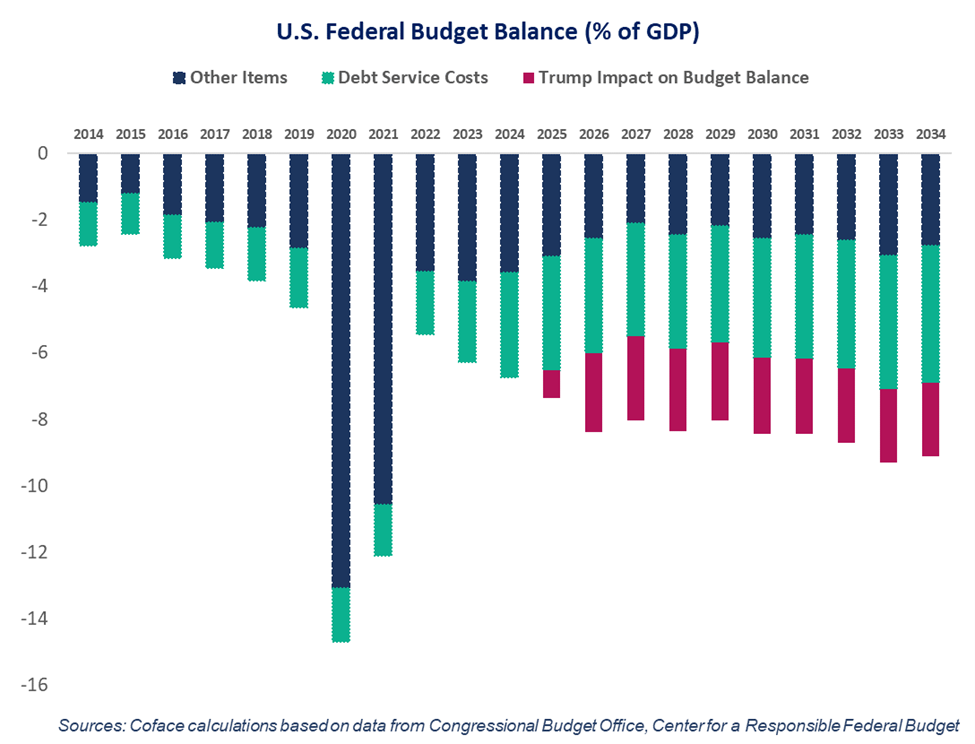

Our real focus, at this stage, should be on the revenue side, where we’re on course for a full extension and expansion of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), including a cut to the corporate tax rate. Economists expect the bulk of the revenue-raising burden will be borne by tariff income. Though the revenue raising potential of wide-sweeping tariffs is nothing to scoff at, it is only expected to cover about half of the foregone tax receipts related to the cuts. The budget deficit, therefore, would likely deepen. It’s worth noting that a Harris victory would not have meaningfully changed this outlook, as her program was also set to deepen the deficit.

The good news

In the short-term (the couple of years following 2026), we expect this extra fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth, even at the price of stronger inflation. More favorable corporate taxation for businesses is expected to strengthen competitiveness (though whether it will be enough to offset higher operational costs due to tariffs is an open question), and income tax affordances could give consumers extra disposable income.

The bad news

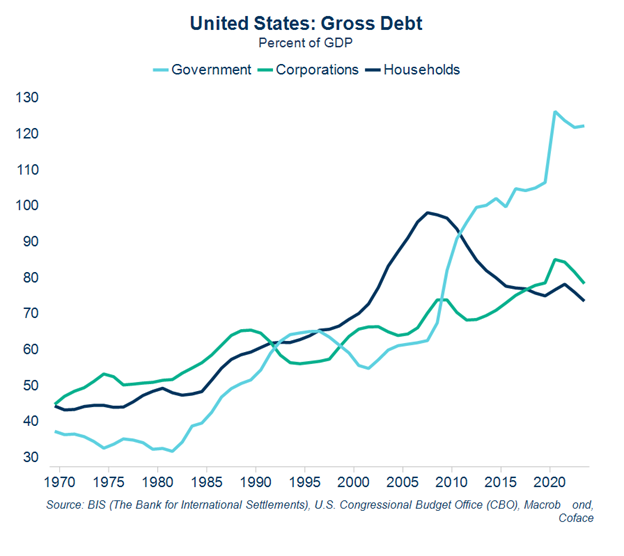

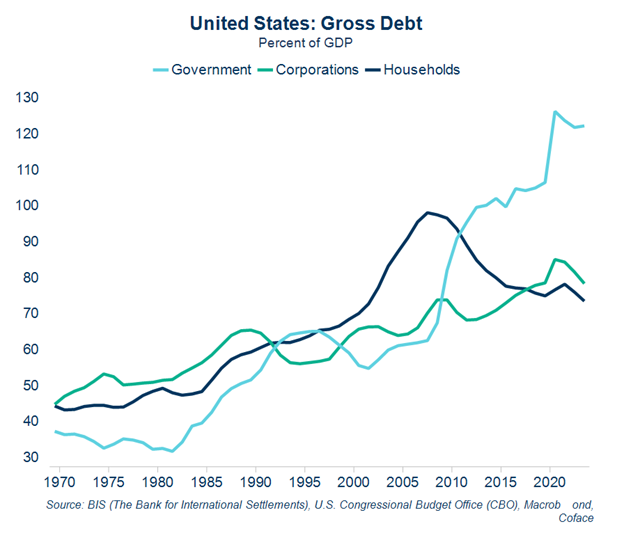

In the long run, adding fuel to the deficit fire takes us closer to the point where the fiscal benefits of the U.S. dollar will be tested. As I mentioned in my pre-election piece, the U.S. dollar’s role as the global reserve currency (i.e. the currency in which the rest of the world wants to hold its assets) provides certain benefits known as the exorbitant privilege. This allows the U.S. government to raise debt easily and cheaply, despite growing concerns for fiscal prudence. Since the subprime mortgage crisis, the U.S. has essentially leveraged the exorbitant privilege (along with a decade of zero-interest rates) to heal private-sector balance sheets (households and, since the COVID-19 pandemic, corporations) at the expense of the government’s balance sheet, through the magic of deficit spending.

It’s estimated that, absent the exorbitant privilege, the U.S.’s debt-raising capacity would be smaller by 22% of GDP. However, the inflation of the COVID years has pushed the world into an era of durably higher interest rates, with the federal funds rate unlikely to go meaningfully below 3% in the foreseeable future absent a recessionary shock.

This higher-for-longer rate environment is putting significant upward pressure on the U.S.’s debt servicing costs (see chart below), which occupies an ever-increasing share of overall expenditure. These costs are also crowding out resources for the government’s other functions. If you want an idea of how this affects firms at the ground level, look no further than struggling pharmacies feeling the squeeze of falling reimbursement rates on prescription medications.

The good(-ish) news about the bad news

In the words of John Maynard Keynes, “In the long run, we’re all dead” or in 21st century parlance, “that’s a later problem.”

It’s hard to say in advance at which point investors will start subjecting the U.S. government to market discipline. For the moment, it doesn’t look like the exorbitant privilege is getting exhausted anytime soon. As bleak as things may look in the U.S., the fiscal picture is not rosier abroad (ask the French and the Italians about their budget deficits). While the renminbi does not pose a material challenge to the U.S. dollar hegemony, we’d be remiss in thinking about this problem exclusively in terms of the U.S. dollar v. other currencies. One possible interpretation of the market’s growing appetite for gold and bitcoin is an erosion of faith in the long-term credibility of fiat currency itself.

U.S. government bonds are the so-called ‘risk-free asset’ that serves as a benchmark by which the riskiness of all other assets is measured. Should the creditworthiness of the U.S. government ever come seriously under doubt, the entire financial system would come under major stress, if not crisis. More likely, a strong fiscal adjustment in the direction of austerity would be necessary to restore confidence, a reality our friends in Europe are starting to confront. In this scenario, the economy would take a proportional hit. But, as I said, we’re not quite there yet.

Marcos Carias is a Coface economist for the North America region. He has a PhD in Economics from the University of Bordeaux in France, and provides frequent country risk monitoring and macroeconomic forecasts for the U.S., Canada and Mexico. For more economic insights, follow Marcos on LinkedIn.